Bone records are one of the unintended consequences of a monumental social experiment.

The Soviet Union was that experiment, an experiment in controlling the economy, controlling ideas, and controlling people. These intentions first coalesced in the 1920s, with the big idea of creating a New Soviet Wo/Man, someone who thought, felt, and dressed how the Party wanted. Apart from the fact that this was always changing, there was always a problem that was never solved - the kids. Pretty much from day one, the state was in a crazy, endless fight with its own youth.

These were the very people who were supposed to be the biggest believers. Instead, many were pushing back, not with a political revolution, but by fighting for their own cultural space in a war for the imagination. The battlefields of this war were music, fashion and personal identity. The state had its weapons - censorship and persecution, but the kids had theirs: smuggled goods, a sense of irony, and a powerful dream of the "Imaginary West".

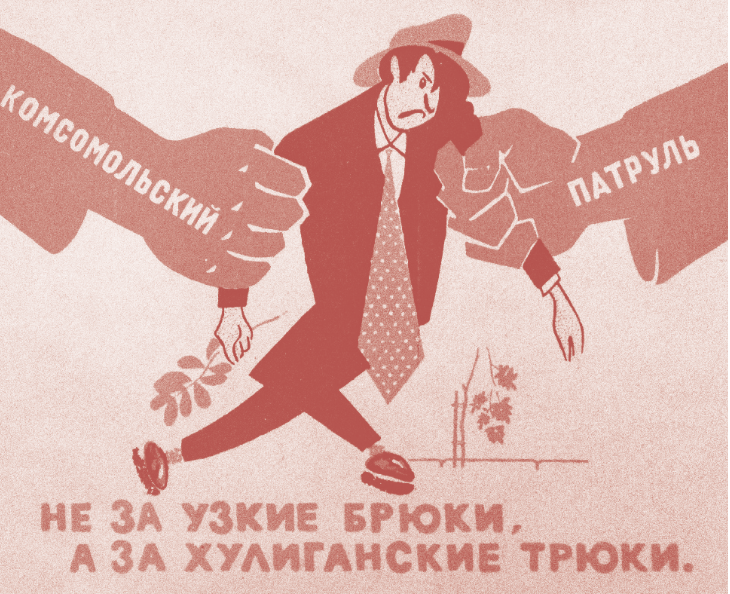

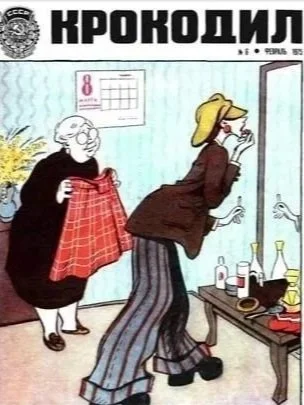

Wasted youth - from Krokodil magazine

This cultural conflict was separate from the much more dangerous business of political opposition. In places like Ukraine, there were secret groups like the Ukrainian Worker-Peasant Union (UWPU) that were talking about real independence and social-democratic reforms. The state's response was brutal - prison or even execution, but that wasn't the path for most young people. Their rebellion was "softer," but it was just as important, perhaps more effective in many ways. It was a cultural, "I'm not playing your game" protest, a protest of non-participation. And in the long run, that quiet countercultural non-conformity did more to unravel the state's authority than any overt political stance ever could.

But do terms such as counterculture, subculture, and youth culture even apply in the history of the Soviet Union’s conflict with its own? In the West, they describe movements in varying relationships to mainstream society. Broadly, countercultures reject dominant values outright, positioning themselves outside the social order, while subcultures express distinct identities—through politics, style, or sexuality—yet remain within it. Yet these labels are unstable, overlapping, and continually redefined, both by those who coin them and those who wear them as badges of defiance.

In the Soviet Union, these distinctions took on a unique resonance. As my friend Artemy Troitsky explores in his book Subkultura, Russian and Soviet history has seen successive waves of youth-driven movements—ideological radicals, mystical sects, hedonistic trend-followers, hippies of the 1970s, perestroika-era rockers, and today’s political activists such as Pussy Riot. The nineteenth-century examples Artemyi identifies—the raznochintsy (intellectual outsiders), the Narodniks (populists who “went to the people”), and religious sects such as the Dukhobors—all expressed different forms of subcultural identity. Brief moments of avant-garde freedom, like in the St Petersburg cafés of 1910-1915, nurtured the Futurists, whose radical rejection of convention was an early echo of later countercultures. David Burliuk’s anarchic verse— “The soul is a pub, The sky – a rag. Beauty is blasphemous crap, and poetry – a worn-out slag.” — even captured a punk spirit decades before its time. But despite their initial support for the Bolsheviks, the Futurists and other avant-gardists were soon suppressed under Stalin’s cultural orthodoxy. The early Bolsheviks, themselves, though they began as fiery countercultural revolutionaries, quickly became the new mainstream and crushed the very forms of non-conformity they once embodied. From the 1930s to the late war years, the space for youthful rebellion had all but vanished, surviving only in the small, secret circles of idealists who dared to dream of freedom.

American Zoot Suiters

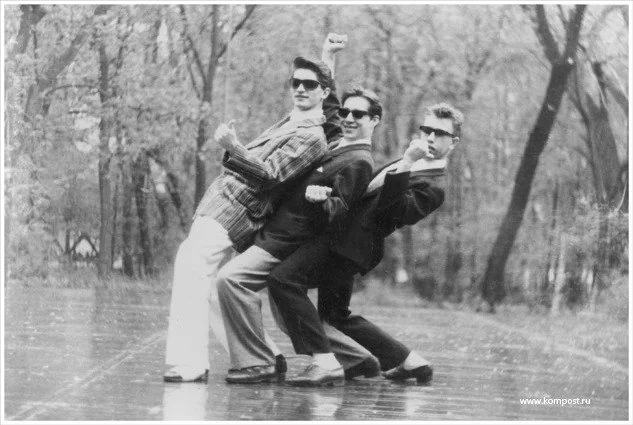

Soviet Stilyagi

The First Rebels: The Stilyagi and the War on Being Different.

As I have written previously, the first youth group to really make the authorities nervous were the Stilyagi, the "style-hunters", the followers of (western) fashion, back in the 40s and 50s. These were city kids, a lot of them from the elite, who couldn't stand the drab, military-style conformity of Stalinist life. Their rebellion was audiovisual. They'd seen American trophy films (movies captured from Germany) and would imitate what diplomats' kids were wearing - they'd create their own bricolage, mix-and-match styles. They copied Western zoot suit jackets with huge shoulders, super-narrow "pipe" trousers, and shoes with the thick soles they called "semolina." Their music was, firstly, American jazz, and later rock’n’roll, both of which the officials hated. This obsession with Western pop culture style wasn't political; they weren't trying to be dissidents; they were just a messy, ambiguous bunch who set their own rules on what looked good. Wild dancing featured heavily.

The state's overreaction was one of moral panic. The regime was obsessed with what Jan Plamper calls "abolishing ambiguity"—it wanted everything to have one agreed, correct, official meaning. And the Stilyagi, with their crazy clothes and unpredictable foreign music, were the embodiment of "ambiguous". The official satirical magazine, Krokodil, lampooned their cartoonish style and pursued them ruthlessly, painting them as folk devils—lazy, parasitic "monkeys", narcissistic spongers, and dangerous "weeds", corrupting the socialist garden. They were bullied, harassed, and could even be prosecuted for khuliganizm ("hooliganism"). This was a catch-all, legal offence: a vague law that pretty much let the state arrest anyone for any kind of deviance.

Dreaming of the West

The Stilyagi—and the subcultures that came after, right up until perestroika, got much of their energy from the "Imaginary West", a place that Alexei Yurchak calls a fantasy realm "simultaneously knowable and unattainable." It was everything the Soviet system wasn't - colourful, free, and full of cool stuff. It wasn't a political fantasy, but a cultural one that was realised mainly through fartsovka, black-market smuggling. Soviet sailors, foreign tourists, and diplomats were the main suppliers of contraband, the sacred goods of youth culture: jackets, jeans, T-shirts, style magazines, chewing gum - and vinyl records, the ultimate prize.

Western records cost a fortune, so in the era of Bone Music, bootleggers such as The Golden Dog Gang were the prime source for the distribution of illicit music, and at times, other Western goods. The bootleggers themselves were a motley crew. Though predominantly young, they were not a youth culture or defined subculture themselves. In the early days, they were mainly anti-establishment music lovers, not dissidents. Later many were fartsovshchiki, in it for the money and selling other illicit goods. Few would have described themselves as Stilyagi - they made and sold many bone records of forbidden Russian music, not just jazz and rock’n’roll, and would have dressed discreetly so as not to be noticed.

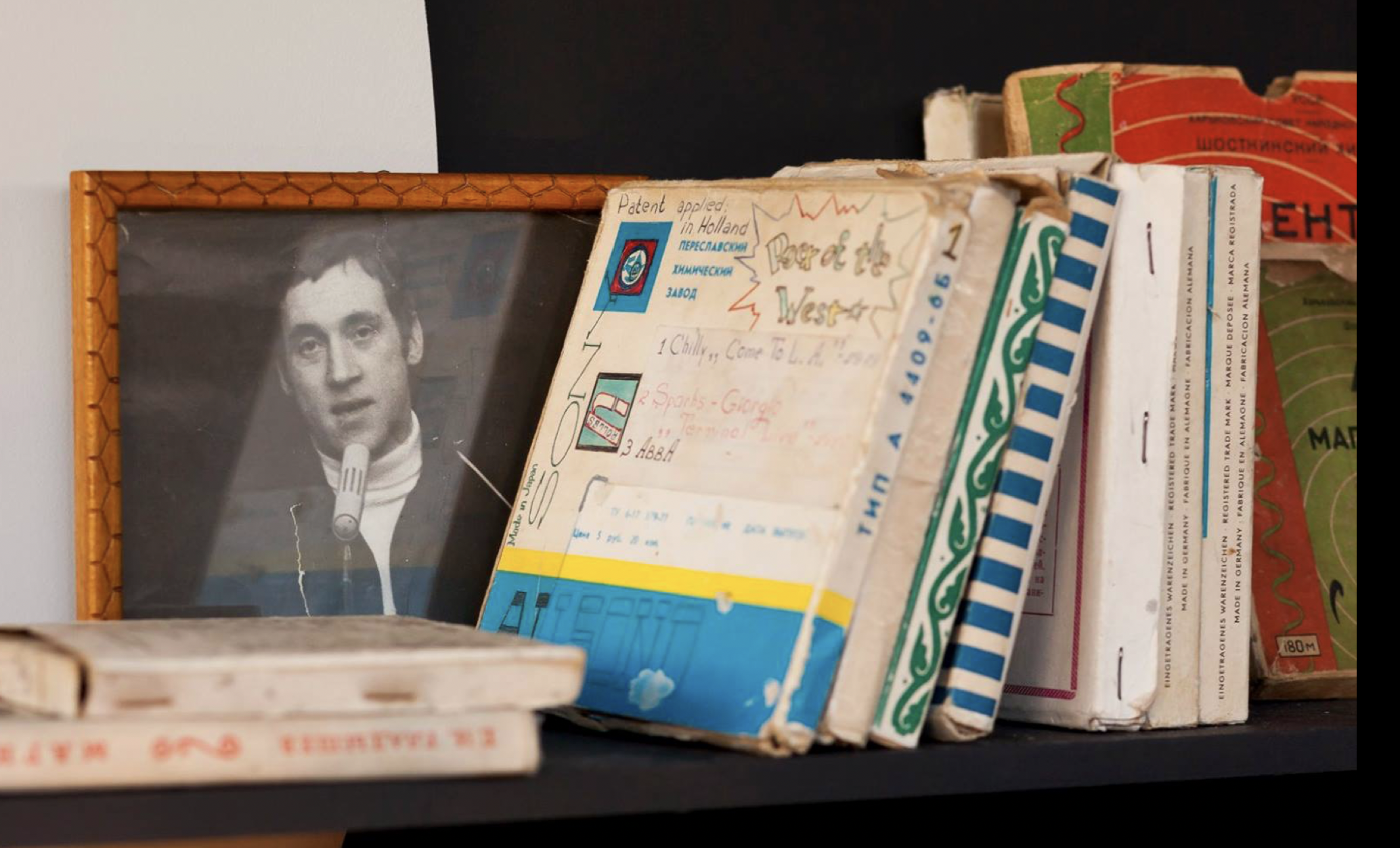

‘Soviet era Magnetizdat’ bootleg tapes

After the era of Bone Music, during the period of ‘Magnetizdat’ bootlegs on tape, the cost of records created whole new social circles - a bunch of friends would pool their money to buy one and then spend all night making tape-to-tape copies for everyone. Some enterprising bootleggers, such as my interviewee Rudy Fuchs, who had once been imprisoned for selling bone records, made money by renting out his extensive record collection by the hour for home taping.

Radio was also a huge source of youthful energy freed from state control. Subsequent to the closing of the Iron Curtain, it was impossible to see the American trophy films, but listening to foreign broadcasts became a crucial form of underground consumption. Some daring individuals even built their own transmitters to broadcast rock’n’roll. Sergei Zhuk says that in the closed city of Dniepropetrovsk, where missiles were built, the KGB was in a panic over such "radio hooliganism." For many others, listening to the BBC and Voice of America was a rite of passage. The result was generations of kids whose cultural imagination was completely alien to, and alienated from, their own government.

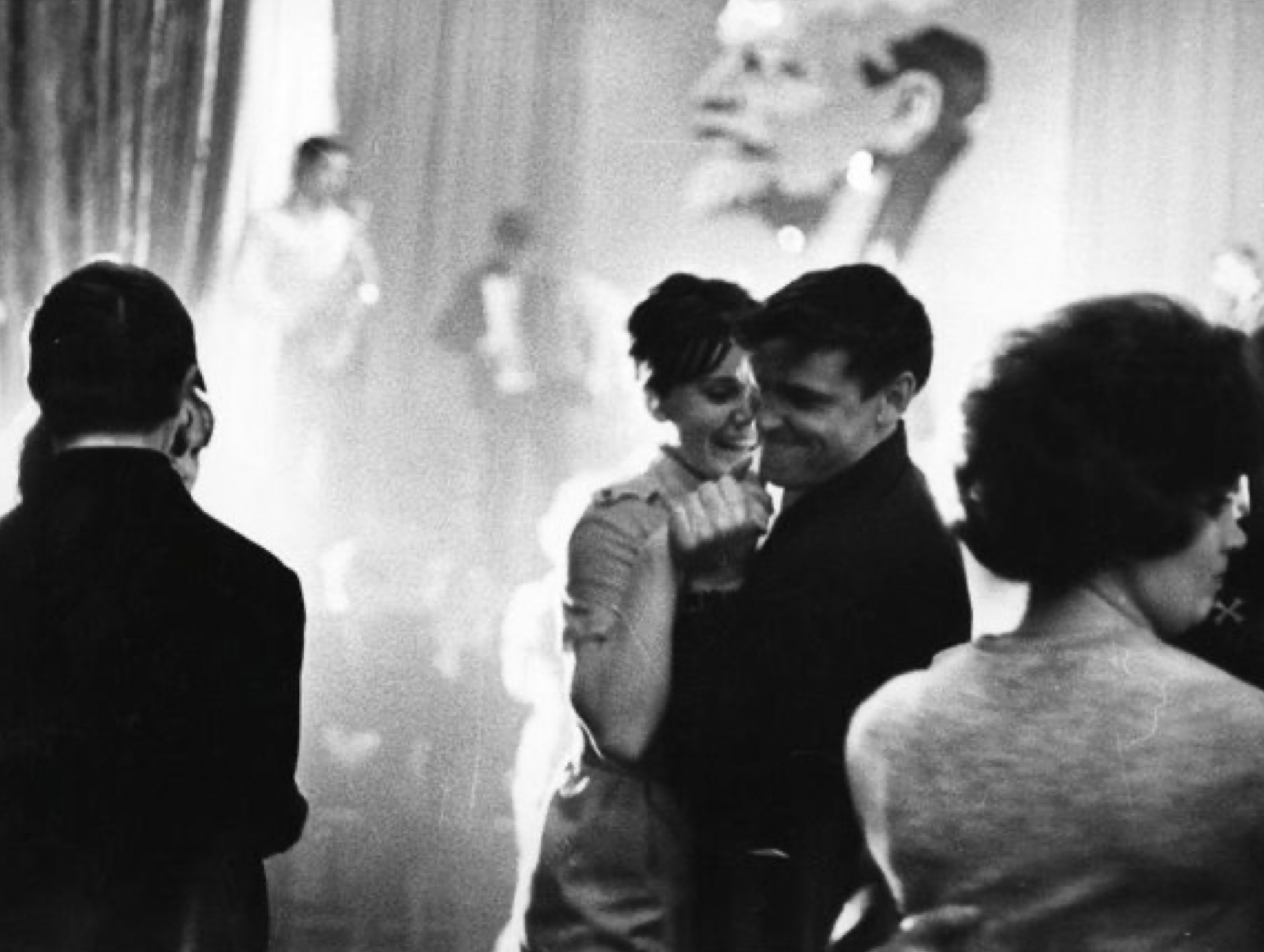

Moscow youth cafe late 60s

The State Fights Back

Faced with this massive and unstoppable demand for Western culture, the state had to change its approach. The hard-line Stalinist way had been to erase things. In Estonia, they banned the word "jazz." The state-run "Eesti Raadio džässorkester" (Jazz Orchestra) had its name changed to "Estrada Orchestra." The band was "reformed" by firing the saxophone players or drowning them out with a wall of strings (the saxophone, a Belgian invention, was seen to represent the very worst of American influence).

It didn't work. By the time Khrushchev came to power in the 50s and 60s, the state had to shift from repression to co-option. Faced with the kids voting with their feet for Western-style fun, the Komsomol (Communist Youth League) decided to sponsor its own "socialist fun." They opened state-run youth cafés and clubs that gave the kids some space to meet and mingle, but they were always a partial concession; the authorities still wanted to control the playlist - and the dancing.

In the more open climate of Khrushchev’s ‘thaw’, a sort of counterculture emerged in the ‘Sixties Generation’ of intellectual artists who had been rather dismissive of the superficial interests of the Stilyagi, Flmmaker Andrey Tarkovsky, poets Joseph Brodsky and Bella Akhmadulina and ‘Bard’ musicians Alexander Galich and Vladimir Vysotsky, attempted to create a culture that was both independent and unique. They were perhaps the last Russian intellectuals to have any sympathy with communism - singer-songwriter Bulat Okudzhava was quoted as saying that the task of his contemporaries was not to destroy the regime but to humanise it.

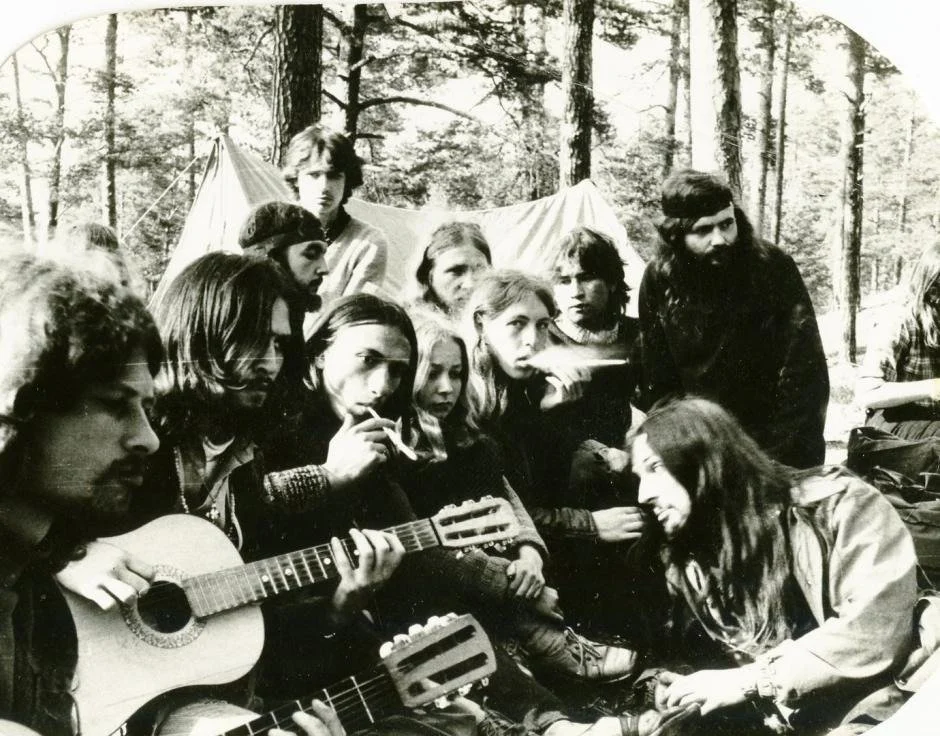

Soviet Hippies

The Next Wave: Hippies and the Generation of Janitors

By the 1970s, during the Era of Stagnation under Brezhnev, a new generation of nonconformists showed up: the khippovniki, or hippies. Their protest was still not about overtly fighting the system, but involved a much more active non-participation. They wanted to be ‘vnye’—both inside and outside the system at the same time - in other words, a subculture. This generation created a loose network of bohemians, artists, and spiritual seekers who. like their Western peers, were all about love, freedom, and sincerity. Their resistance was social escapism. They famously became the generation of street cleaners and gatekeepers. Smart, educated kids from good families would refuse to join the Komsomol or get a professional job. Instead, they'd get work as janitors, night watchmen, or boiler-room operators because these jobs demanded zero ideological loyalty and left them with free time for their real lives: writing, art, relationships, philosophy, and, of course, music. Their soundtrack was no longer jazz or the songs of the bards but the homegrown Russian rock made by bands like Mashina Vremeni (Time Machine). Aquarium, Auktyion, and later, Kino, all of whom were to become underground stars, via massive distribution of bootleg tapes. Their lyrics weren't attacking the state; they were singing about personal life—sincerity, love, loneliness. In an official culture built on heroic, public statements, celebrating collective ideals, just being honest about your feelings was a radical act.

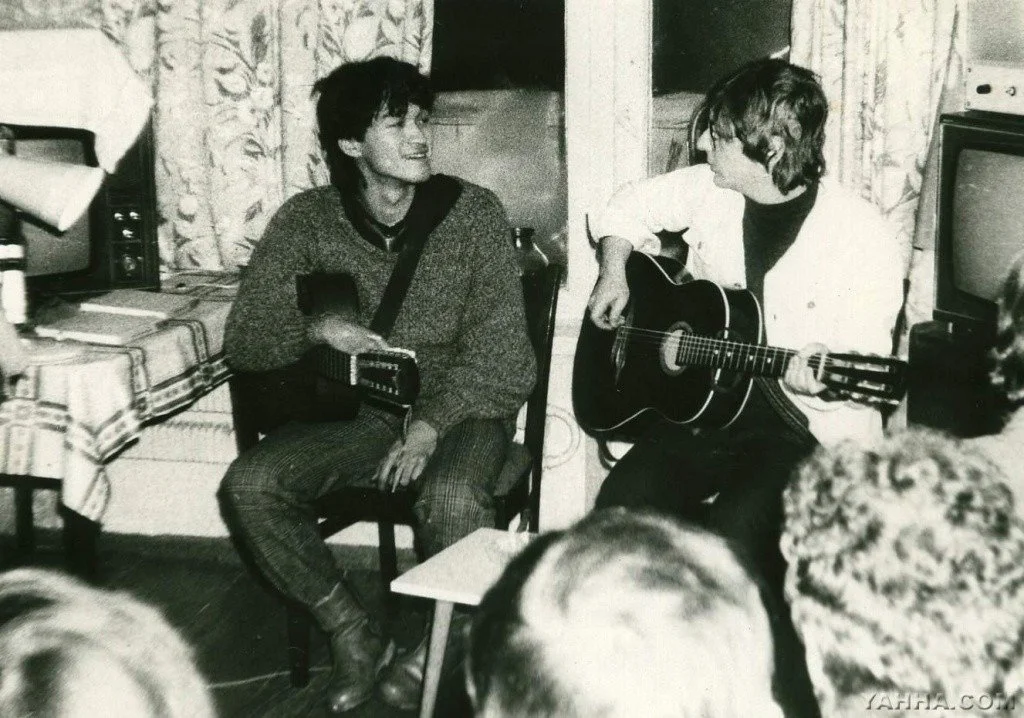

Boris Grebenchikov at an Aquarium apartment concert

Victor Tsoi of Kino at an apartment concert

Right back to the post-Stalin years, musical gatherings were happening in secret. The stilyagi held clandestine dance parties in empty flats, and low-key, intimate ‘apartment’ concerts became increasingly popular through the 60s, 70s and 80s. The state, for its part, tried to control this by forcing the rock bands into the official system, which just created a split between official rock and the real underground.

The Komsomol list of banned rock bands

Things Get Weird

The 70s and 80s saw an opening up to foreign pop music, often with unintended consequences. The rock opera Jesus Christ Superstar became popular because Ian Gillan of Deep Purple sang Jesus’s part. Largely apolitical rock kids started wearing crosses and reading the Bible, grabbing onto any identity the communist project had explicitly rejected. Official and semi-official deals between the state Record company Melodiya and Western labels introduced the delights of ABBA, Boney M and various other unthreatening pop acts to the Soviet public. But the floodgates were definitely not wide open. Sergei Zhuk's study of the closed city of Dniepropetrovsk describes how the KGB, terrified of ideological pollution near their missile factory, went completely overboard. During their anti-fascist panic in the 80s, Komsomol officials handed out blacklists of Western bands, banning groups like AC/DC and Kiss on the basis that the lightning-bolt logos were covert Nazi SS symbols (given the monumental tragedy of the Second World War, accusations of Nazism were, and remain, a perennial way of defining an enemy). It completely backfired. The bans just made the bands seem even cooler, and showed the kids that the authorities were clueless.

By the 1980s, the last Soviet generation, as Alexei Yurchak describes it, had perfected a cultural response to this bizarre world: stiob, a complex, in-the-know irony, a deliberate overidentification with official symbols, to mimic the system so perfectly that no one could distinguish a loyal supporter from a total subversive, a sophisticated response to a system that demanded loyalty but didn't seem to care if it was sincere.

Ravers at The Gagarin party

The Final Act: Ironic Ravers and the Gagarin Party

When the Soviet Union finally collapsed in 1991, it left a void. The communist, socialist cultural story was over and the official vs. underground dynamic that rock music had depended on vanished, throwing the scene into confusion. The birth of post-Soviet youth culture rose from those ashes. Perhaps the perfect symbol of this was the "Gagarin Party" of 1991. This legendary rave organised by veterans of the old underground art scene, was held in the "Cosmos Pavilion," a holy shrine to Soviet technology. As thousands of kids danced to imported Western techno, the organisers projected a giant image of Yury Gagarin over the crowd, the ultimate act of stiob. They weren't making fun of Gagarin but “freeing the symbolic meanings" of the past. The last Soviet generation was, in effect, "sampling" the Soviet project. They tossed out the boring ideology but reclaimed the heroic, cool parts—like the image of Gagarin—as their own, mixing it in with global Western culture.

From the stilyagi's crazy orange jackets all the way to the Gagarin Party, the story of Soviet youth culture is one of non-stop, creative adaptation. The state's big plan to build a perfectly unambiguous world failed because ultimately culture cannot be controlled, can't be limited to one meaning. The kids' obsession with Bone Music, Western fashion and wild dancing wasn't some big political plot. It was just being human. It was a desire for identity, for style, for fun - borrowed and adapted until the time came when it could become homegrown.

In the end, the system wasn't brought down by an army. It was hollowed out from the inside, one smuggled record, one pair of blue jeans, and one dance party at a time.

Further Reading:

Stephen Coates: Bone Music

Artemyi Troitsky: Subkultura

Alexei Yurchak: Everything was Forever Until it was No More

Julia Furst: Stalin’s Last Generation

Sergei Zhuk: Rock and Roll in the Rocket City

Post Script

As I have noted elsewhere, I see the true ‘Bone Music’, the forbidden songs cut on x-ray records, not just to be American and British Jazz and Rock’n’Roll, but Russian music - the songs of emigres and underground singers. That was enjoyed by many ‘ordinary’ citizens, who would not have defined themselves as Stilyagi or of any particular subculture, and who were of all ages.