FACE, another rapper and a vocal critic of the Russian invasion, told Rolling Stone:“If democracy can win in Ukraine, then our people can fight for our own freedom, that’s one of the reasons right now that Russia invades Ukraine”

Both artists now live outside Russia and face designation as 'foreign agents’ along with many others - and it’s not just the young. Veteran Russian pop star Alla Pugacheva, 73, who has sold more than 250 million records, took a stand after her husband denounced the conflict:

“I am asking you to include me on the foreign agents list of my beloved country.

Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra and chief conductor Kirill Petrenko has issued statements condemning the invasion; opera star Anna Netrebko, who has past ties with Putin, has withdrawn from all engagements, stating: ’This is not a time for me to make music and perform.

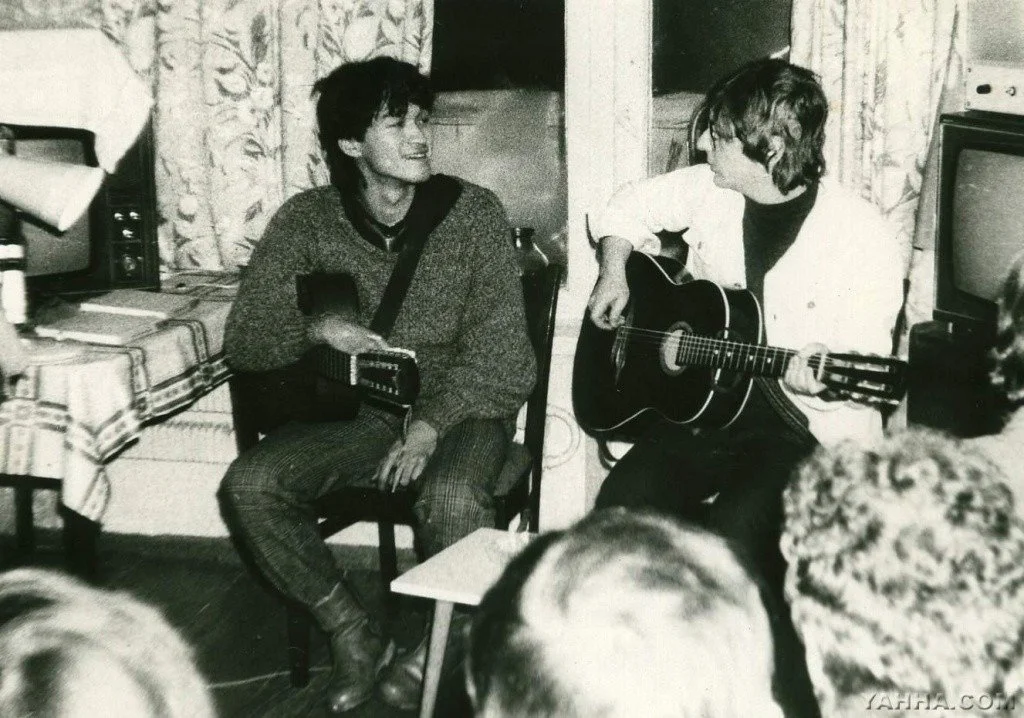

Rock star Yury Shevchuk, the frontman of 1980s band DDT, already known for his verbal confrontations with the governing power, opposition to Russia’s annexation of Crimea and support for anti-Kremlin activist collective Pussy Riot, was recently arrested after he criticized the Russian President at a concert:

“The motherland, my friends, is not the president’s ass that has to be slobbered and kissed all the time, the motherland is an impoverished babushka at the train station selling potatoes.”

He now stands charged with “discrediting” the Russian military. Russian authorities have launched more than 2,000 such cases. Over a hundred others face up to 15 years in prison under tougher criminal legislation that bans the spread of “fake news” about the military.

Many Russian musicians who have denounced the conflict had their shows cancelled or left the country and there is a wider collection of Russian artists and culture workers who are taking a stance. An open letter signed by over 17,000 states:

’We, artists, curators, architects, critics, art critics, art managers - representatives of the culture and art of the Russian Federation - express our absolute solidarity with the people of Ukraine and say resolutely “NO TO WAR!”. We demand an immediate stop to all hostilities, the withdrawal of Russian troops from the territory of Ukraine and the holding of peace talks.’

Many have been sacked or been unable to work. Kiril Serebrennikov one of Russia's leading theatre and cinema directors who is known for his liberal and LGBT-friendly stance had his ballet ‘Nureyev’ cancelled by The Bolshoi after he criticized the invasion

Even public use of the word ‘war’ comes with risk of detention.

Alas, the cultural effects are not just in Russia. It's possible to unequivocally condemn the invasion whilst acknowledging its origins are complex and the west has played more of a part in its causes than our mainstream media allows. It has also been very disappointing to witness ludicrous black and white thinking applied to ’Russians’ (millions of whom don’t support Putin and / or live abroad), and to Russian culture here in the UK. I was personally challenged about the appropriateness of promoting a show by Russian theremin player Lydia Kavina (a British resident of over 25 years). A friend who is living in semi-exile in Turkey and resolutely anti-war was ‘disinvited’ from a festival he had been booked for in Bournemouth because he was Russian. I even heard recently that a well-known hipster store in London has taken books with Russian content (such as Fuel’s ‘Russian Criminal Tattoos’ and ’Soviet Bus stops’) off its shelves.

My friend Alex Kan, the BBC’s Russian arts correspondent is devastated. Born in Soviet Ukraine, like many others, he relocated to Russia and has moved back and forth between the two countries and the UK since. He has family and friends in both and considers their cultures and languages completely intertwined - for him, this conflict is more like a civil war. He has spent his entire life promoting cultural connections between Russia and the west and now feels it is all in ruins. I have spent a lot of time in Russia, I have many Russian friends. The scale of what they are experimenting does not match what the people of Ukraine have faced but many have felt they have to leave, and those that can’t are living in fear and despair.

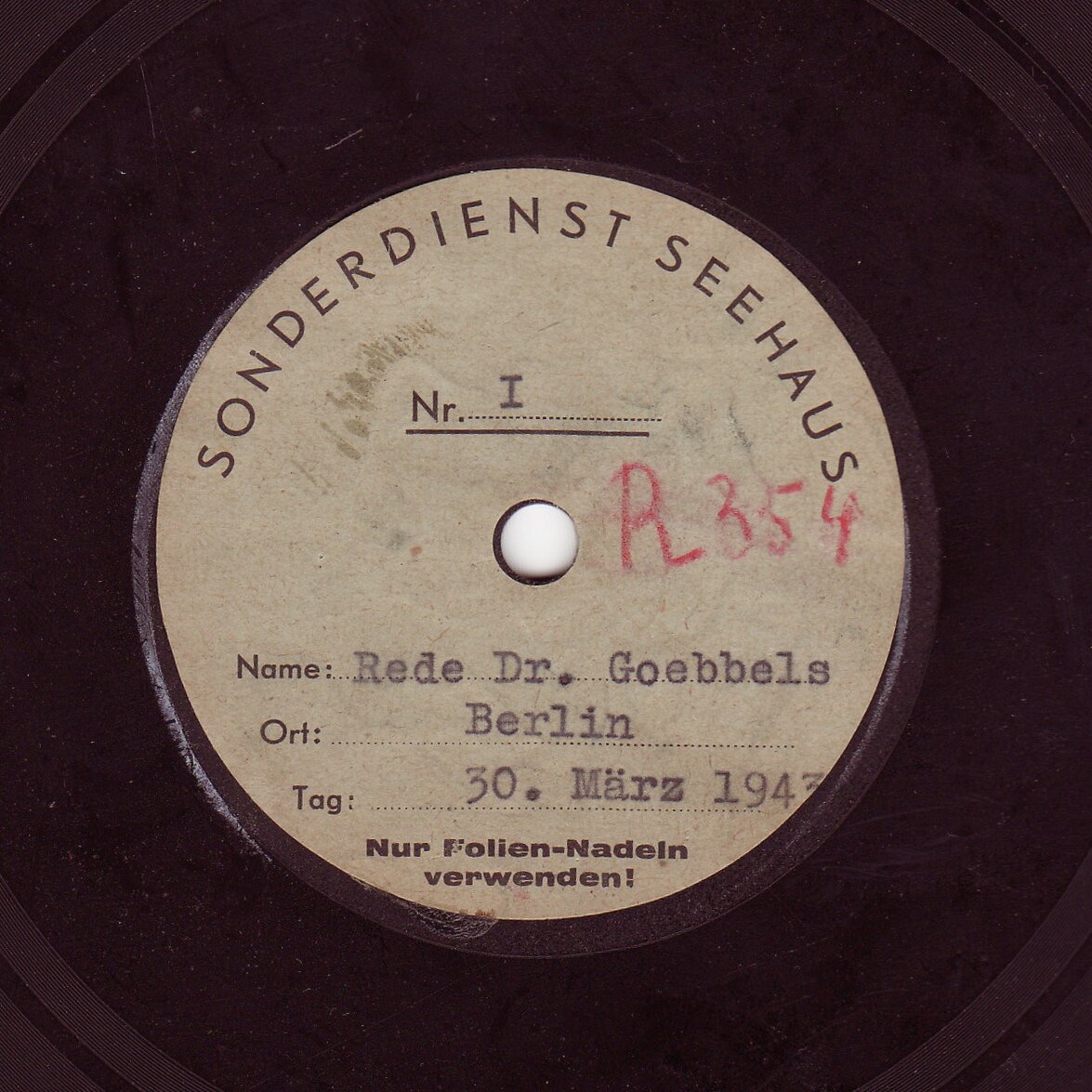

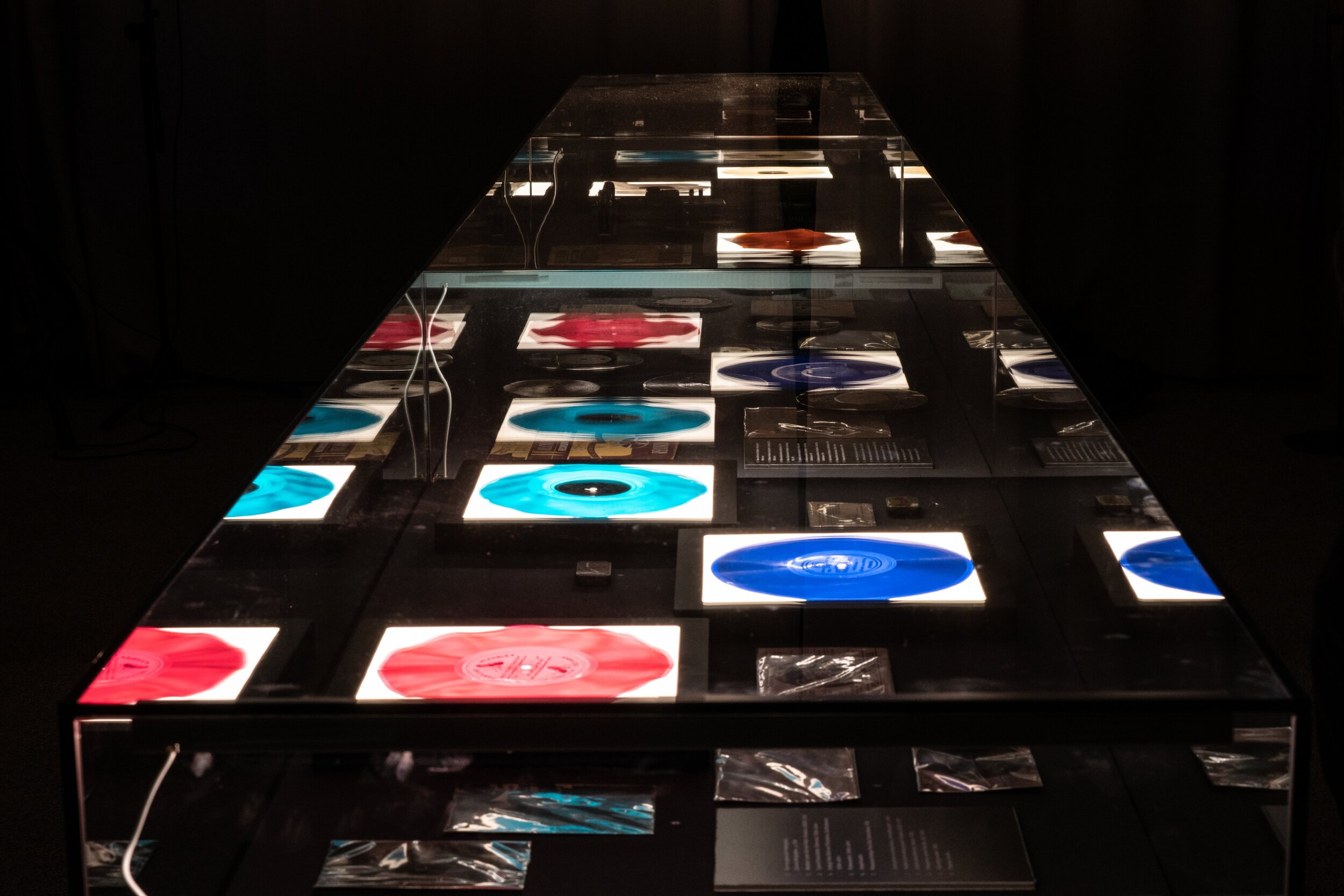

So, to go back to the start, what, if anything, has the history of Bone Music to say about what has happened?

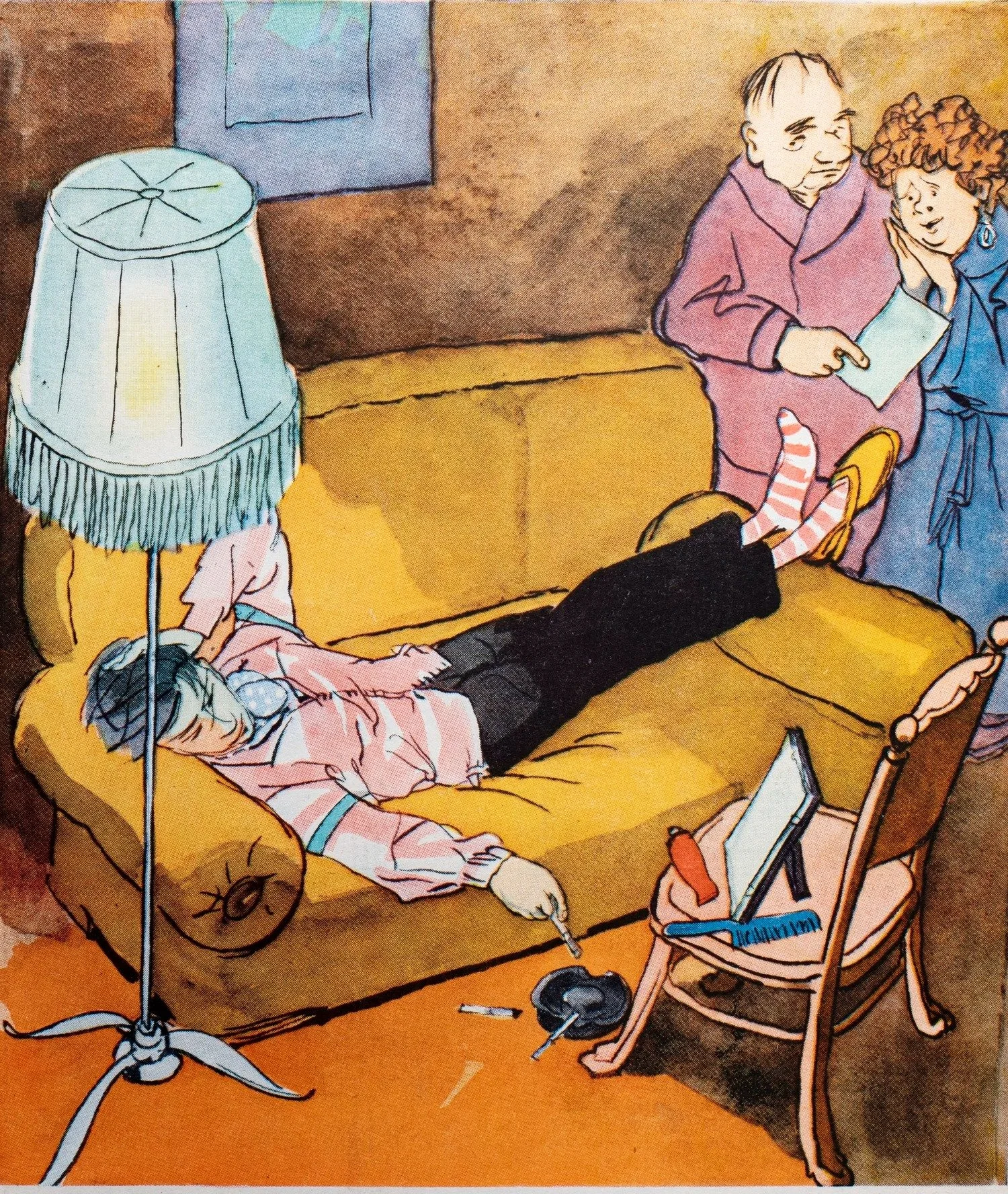

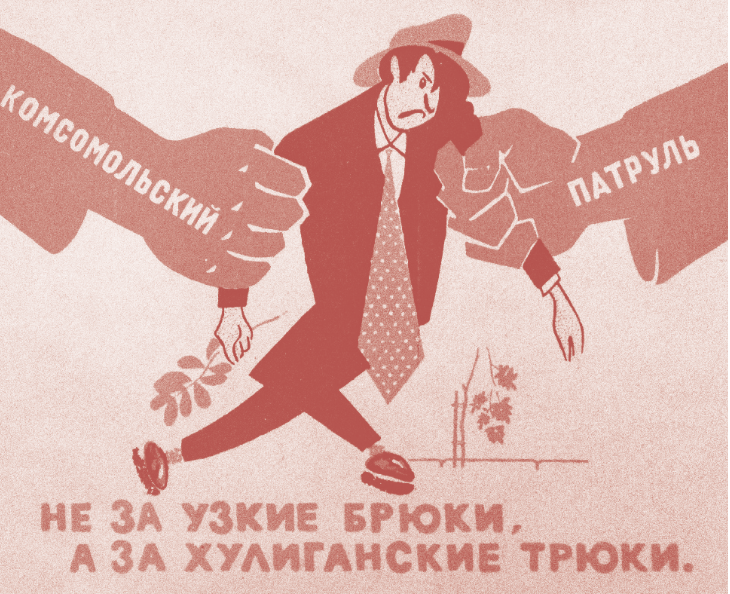

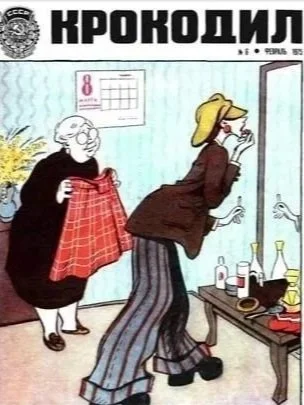

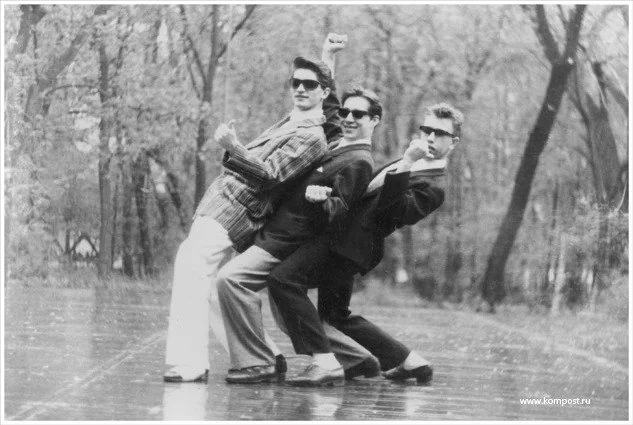

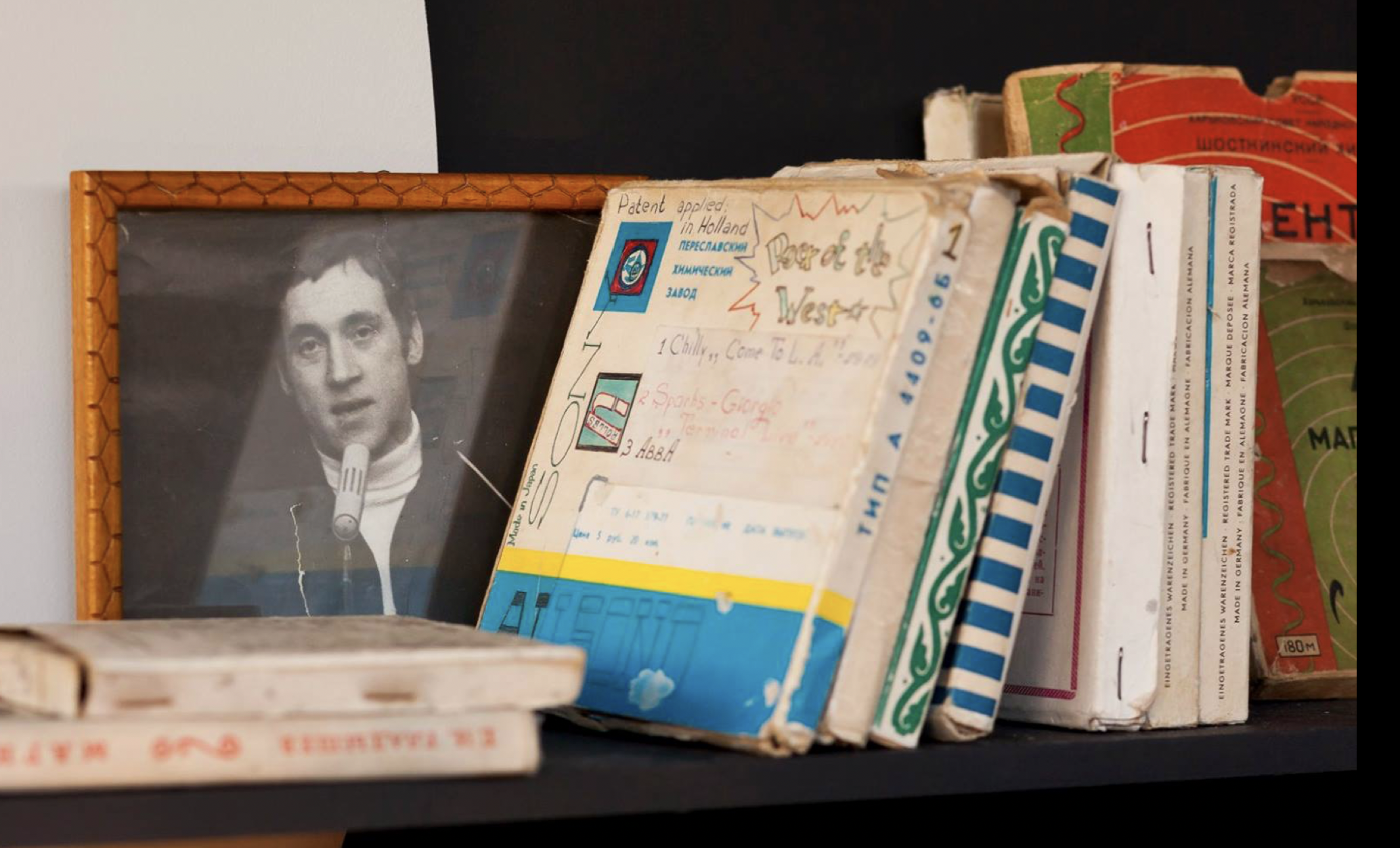

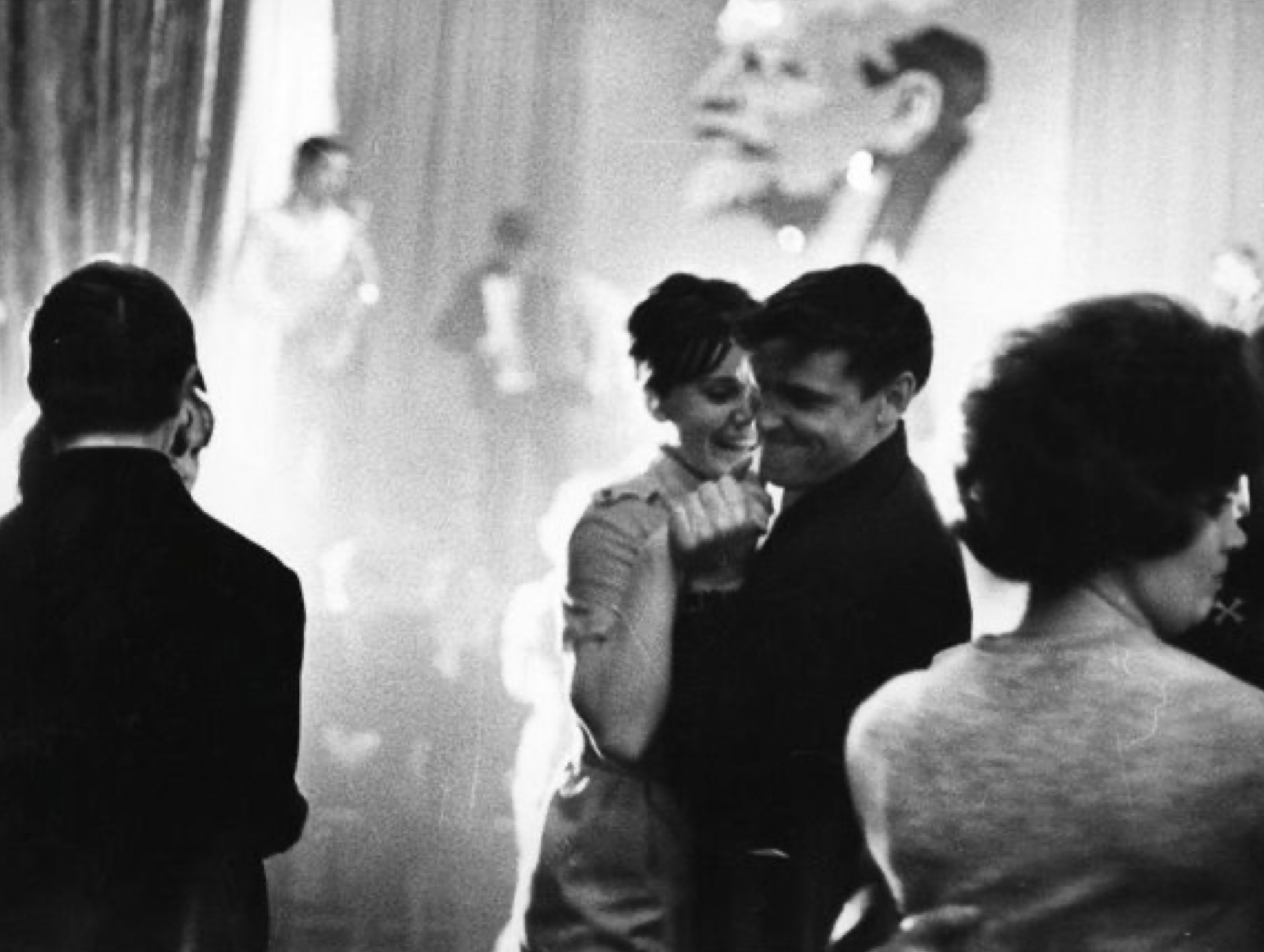

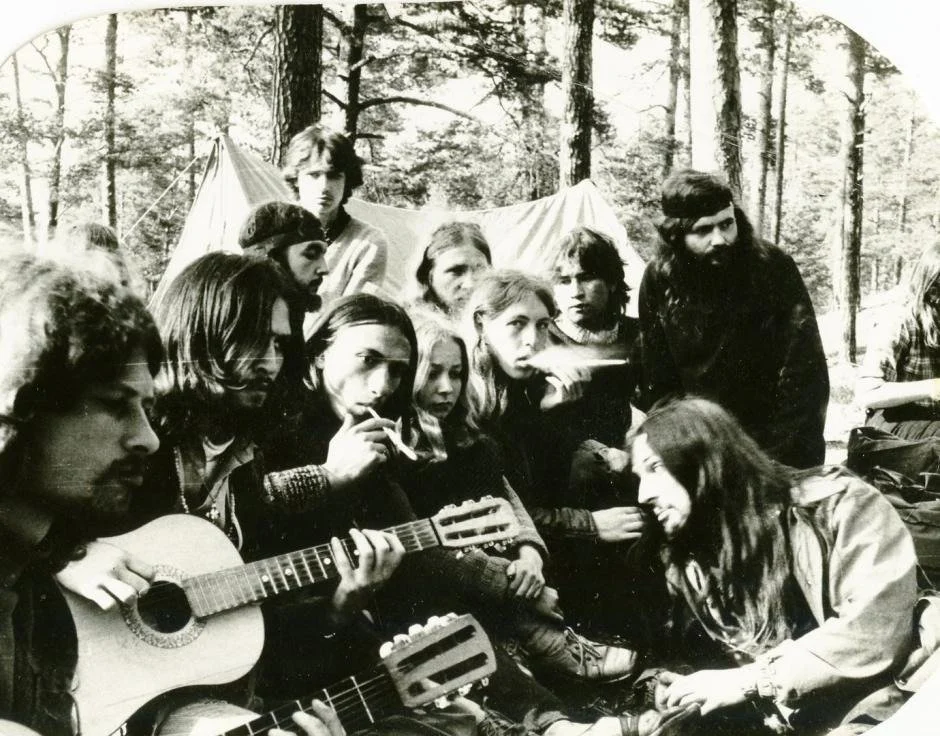

The x-ray underground of the 40s, 50s and 60s was one of the few ways to express protest (even though that protest was usually non verbal). Whilst it would be way too dramatic to claim it had a pivotal role in the changes that were to come, it was certainly one of the Samizdat roots that eventually flowered into mass cultural disobedience, and it remains symbolic of the way that music can help bring about transformation.

That transformation took place over decades, but perhaps In our speeded-up world, it can happen much more quickly, especially if those to whom it matters the most - the young - believe that it can.

Culture is one of the most important things that connects us all - beyond, ideology, nationalism, politics and beyond conflict.