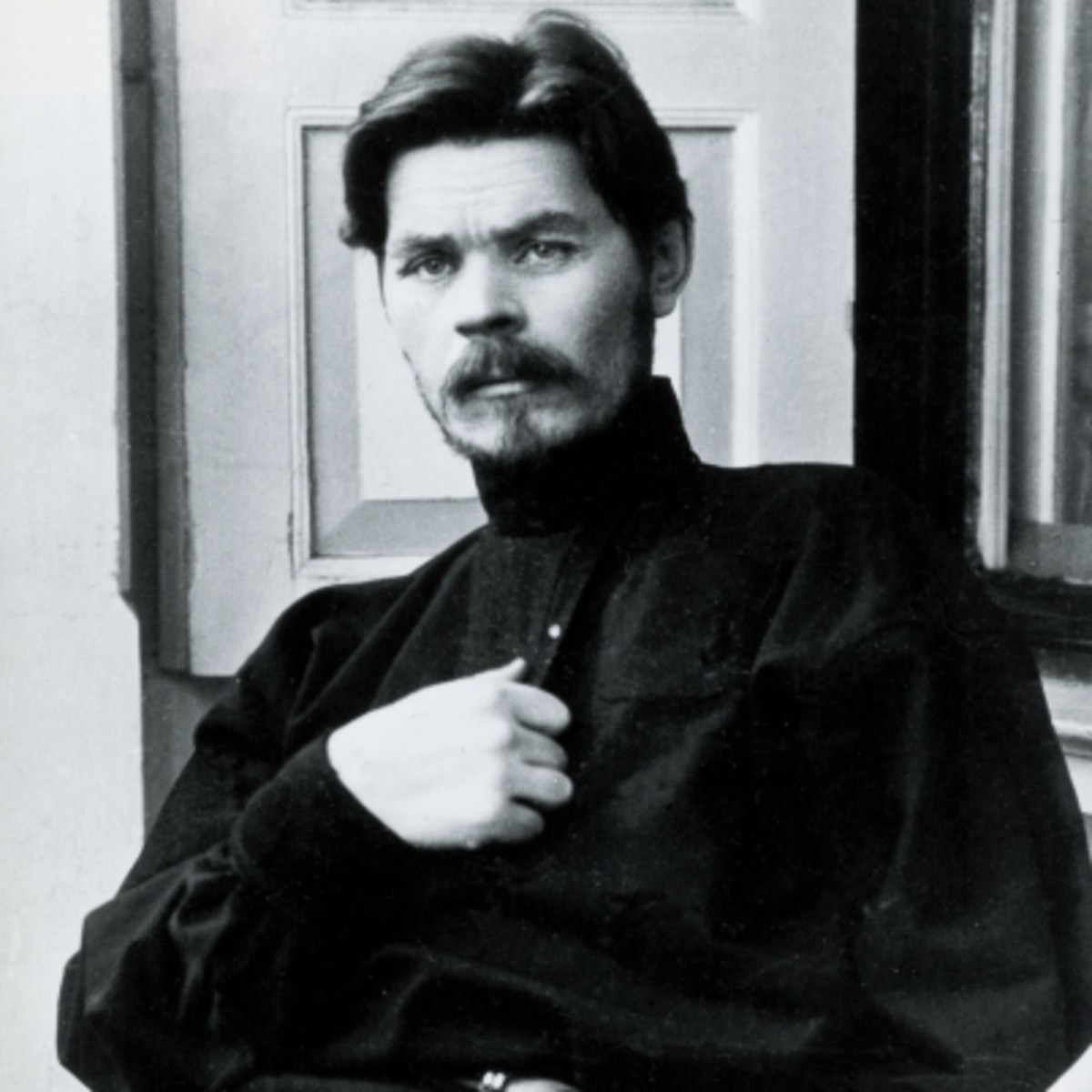

Vladimir Vysotsky

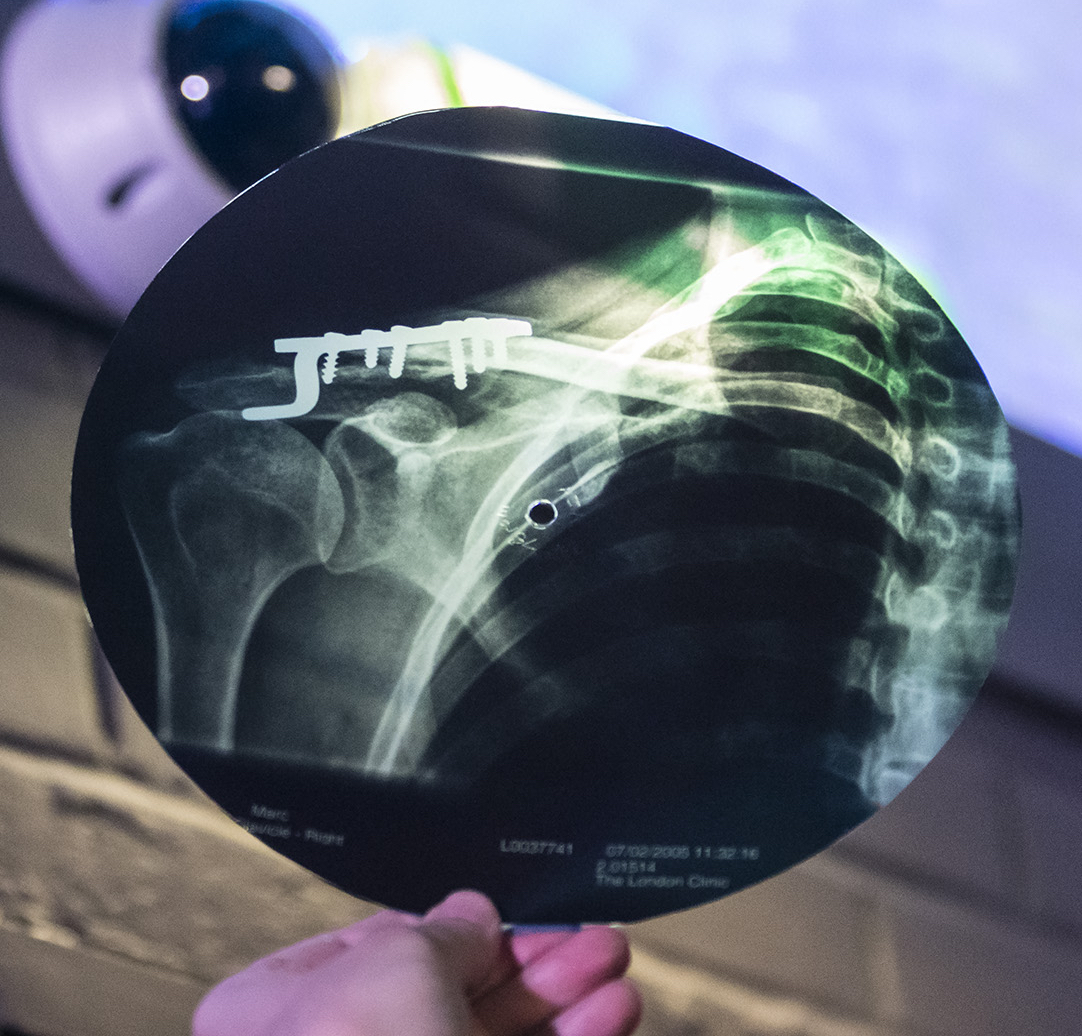

Of the various types of music that appeared on x-ray, the ones that have most been written about in the west are jazz and rock’n’ roll. That is natural because it fits wth a western view of cold war culture but it is only partly true. I have written HERE about the Russian emigre songs (mostly forbidden) that were the most common recordings found on bone records.

But there was another type of music that was perhaps more important in terms of dissidence, even though it was less common on x-ray. This was the music in the ‘blatnaya’* style - a genre that originated inside the Soviet Union and was always deemed completely unacceptable for recording or distribution: the Odessa ditties, the urban romances, the criminal and gulag chanson - the ‘Yard’ songs.

These songs might have been forbidden from being recorded but they were sung live in the courtyards and communal places where ordinary people gathered out of sight of the authorities. They were not necessarily overtly protest songs as was understood in the west; they were prohibited just because they were about real-life in the USSR with lyrics about love, lust, violence, death, criminal culture, suffering. They revealed the dark underbelly of the utopian communist dream and that was of course off limits. Further, they often contained criminal slang, swearing or coarse jokes at the expense of the Soviet system and officials. Maxim Gorky, the social realist ideologue, had declared in the early 30s that any art form critical of the Soviet system should be banned. Often their tunes were old melodies whose life stretched back to the era before the revolution, tunes everybody knew and loved and were adopted with new lyrics as the years went by. Many are still known and loved in Russia.

The continued existence of these songs was a kind of collective unspoken act of resistance. Singers could be punished (some were sent to gulags some exiled, others shot), songs could be forbidden (whole books listing forbidden songs were produced each year) but it did not mean they were forgotten. The songs lived on by being performed clandestinely in communal places where underground culture was passed from generation to generation. Sheet music of the most popular tunes was secretly produced, circulated and exported so that émigré singers could make recordings abroad and these be smuggled back in to be copied and distributed on x-ray.

Our friend the scholar Maxim Kravchinsky (see www.kravchinsky.com) is a world expert on this genre of music - and on Russian emigre songs. He introduced me to Eleonara Filina, a journalist and singer of yard songs, who explained how the soul of Russians oppressed under the Soviet system lived on in part by the singing of yard songs:

“Why the yard? Because Soviet people had a tradition of gathering after work or on weekends in their courtyards. That was in our nature, thanks to the fact that there were a lot of communal flats perhaps. We lived like this, crowded, there were so many of us. Apartments were small. The Soviet people were very sociable. They would go out into the yard of their apartment buildings and sit and sing these songs together because TV was not enough, radio was not enough. They were sung wherever people gathered, in the yards, in the kitchens, in the pioneer camps, in the prisons

The thing is, the Soviet establishment was trying to show life as a candy wrapper - everybody's happy, everything's fine, there is no problem, we have a brilliant future. And these songs were about the realities of life, how people really lived. They were about betrayals of love, about suffering, about how people were sent to jail, you know. Everything was expressed in the songs. That’s why they were forbidden.

Moreover, during the years of repression, the intelligentsia were in prisons, along with criminals. They heard these songs and when they came out of prison, they sang them just as the criminals did in the yards. Their kids, the neighbours heard the songs, and they loved to learn them and sing them too.” After all, almost every family had at least one member in the camps

*‘Blatnaya’ does not seem to have any simple English translation but ‘Blatnoy’ initially meant a criminal who holds authority amongst other criminals in labour camps, colonies or prisons. It is a romanticised vision of criminal life and the word ‘Blat’ apparently has connotations of ‘blood’, ‘bone’ and ’bread’ - perhaps implying something essential, something visceral, something of ‘the soul’? I’d be eager to hear from Russian friends on how they understand this word.

—————-

Prisoners at the White Sea Canal Prison C1933 Photo: Oleg Klimov / Russian State National Library, St. Petersburg

Songs like Yury Nikulin’s "Postoi Parovoz” (Hold on, Steam Train), a criminal song of regret, became hugely popular through being sung in the yards.

Don't wait for me Mother

Don't expect me to be the nice boy I used to be...

A dangerous swamp has swallowed me up.

And my life is a constant gamble

One of the most famous criminal songs sung in the yards was ’Murka” which told the tale of a faithless female member of a criminal gang to a tune originally composed by Oscar Strok. It was performed in many versions by underground and emigre singers and even by official singers like Leonid Utyesov.

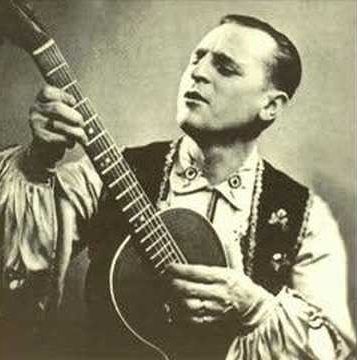

Underground singers like Arkady Severgny became hugely popular without any official acknowledgement by recording and performing yard songs secretly. Vladimir Vysotsky, probably the most famous actor and singer of the 60s, started out as a yard singer before he began composing his own songs, which themselves were a stylised version of the yard songs. Vysotsky’s music was officially forbidden for many years, but even government apparatchniks listened to it secretly.

How?

On x-ray discs and magnetic tape bootlegs.